Original Items: one-of-a-kind set. This comes "straight out of the attic! This grouping belonged to FRANK J CANOVA, #32918460 from Patterson, New Jersey. What this extraordinary solider experienced in a German POW camp for 15 months, we will never know, but he is a real hero for certain. This amazing grouping includes the following:

Private Canovas WWII tunic with his initials and number (FJC 8460) complete with all buttons, insignias, badges including his 36th Infantry (Texas Division) shoulder patch and 7th Service Command patch.

Decorations and Citations include: European African Middle Eastern Campaign medal with two battle stars for campaigns in Naoples-Foggia (GO 33 WD 45) and Rome-Arno (GO 33 WD). American defense ribbon, Presidential until citation, Good conduct and his Combat Infantryman Badge (CIB) .

Right sleeves shows 5 stripes for 30 months of overseas service.

Paperwork includes:

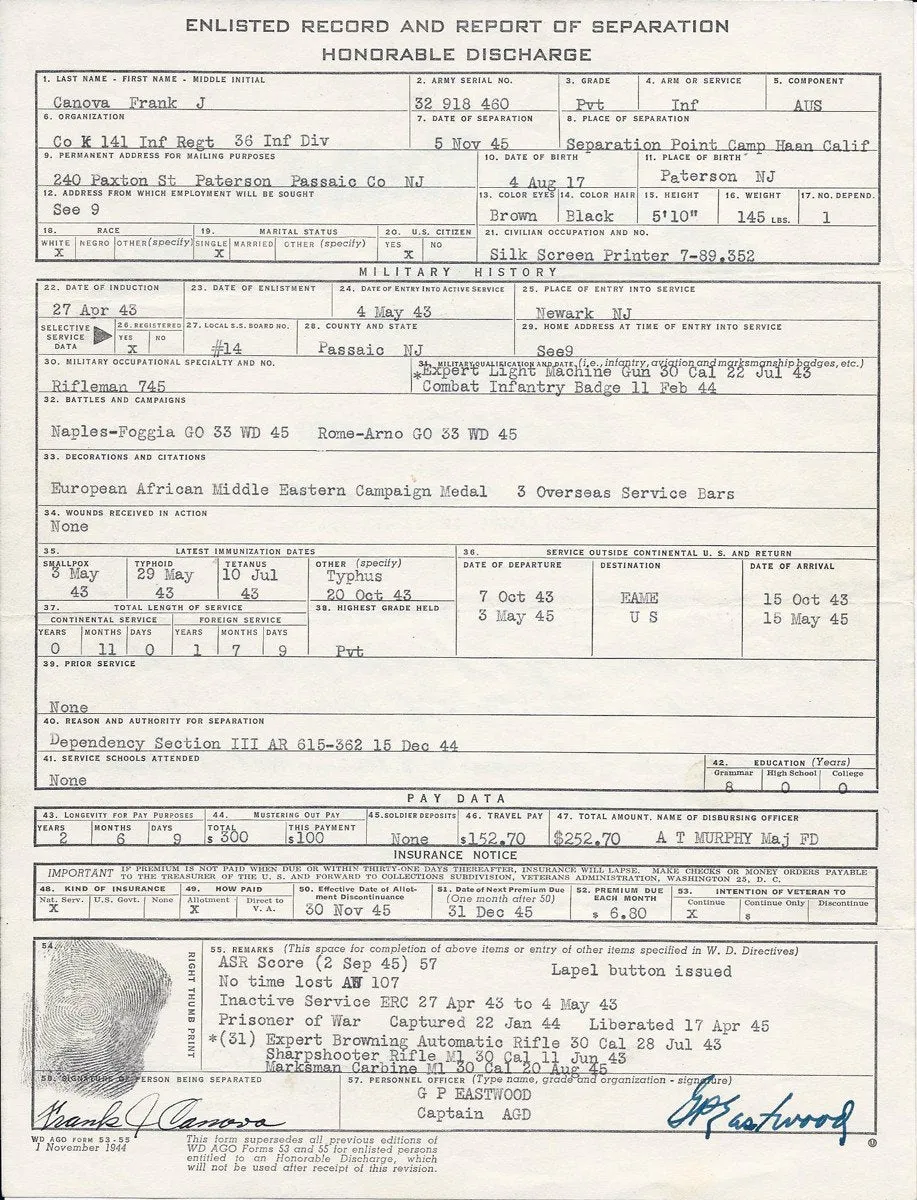

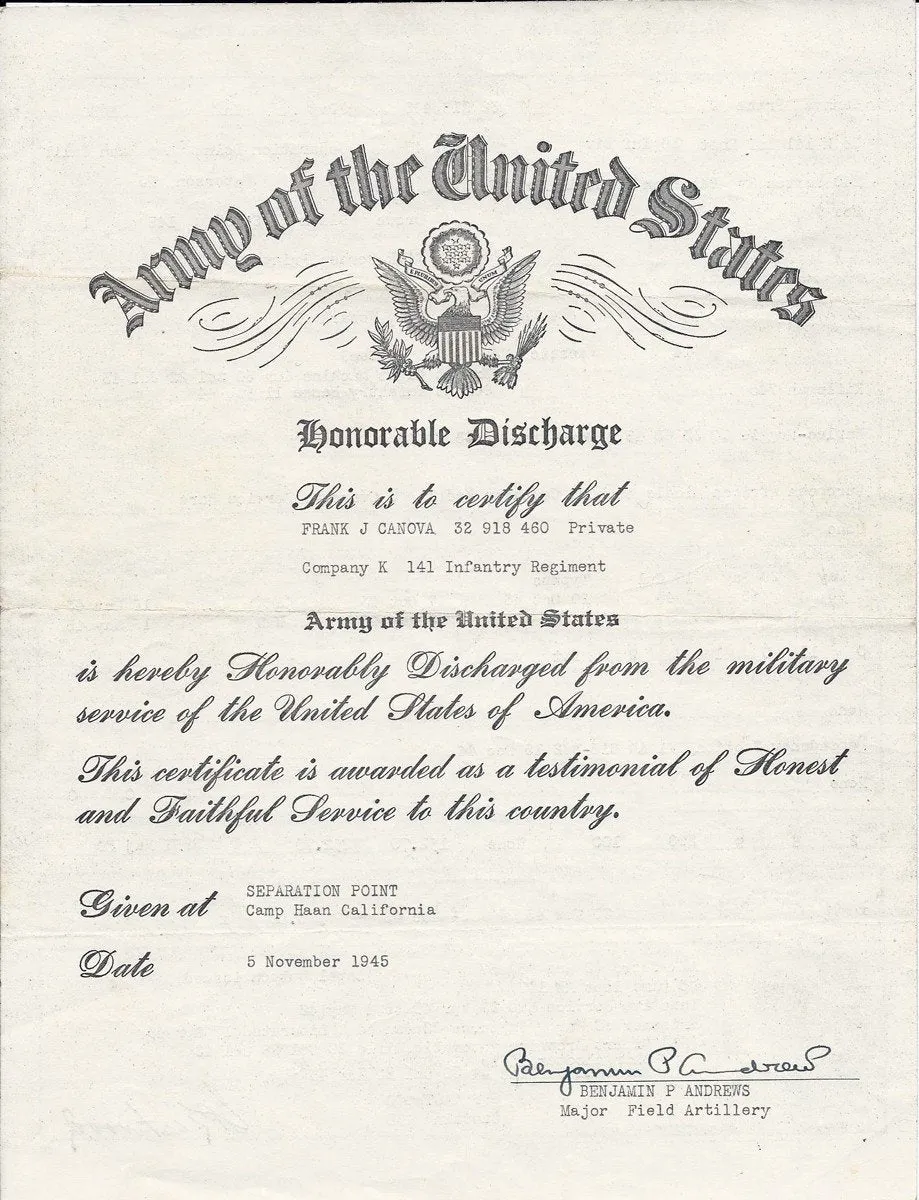

Original Enlisted Record and Report of Separation, Honorable Discharge.

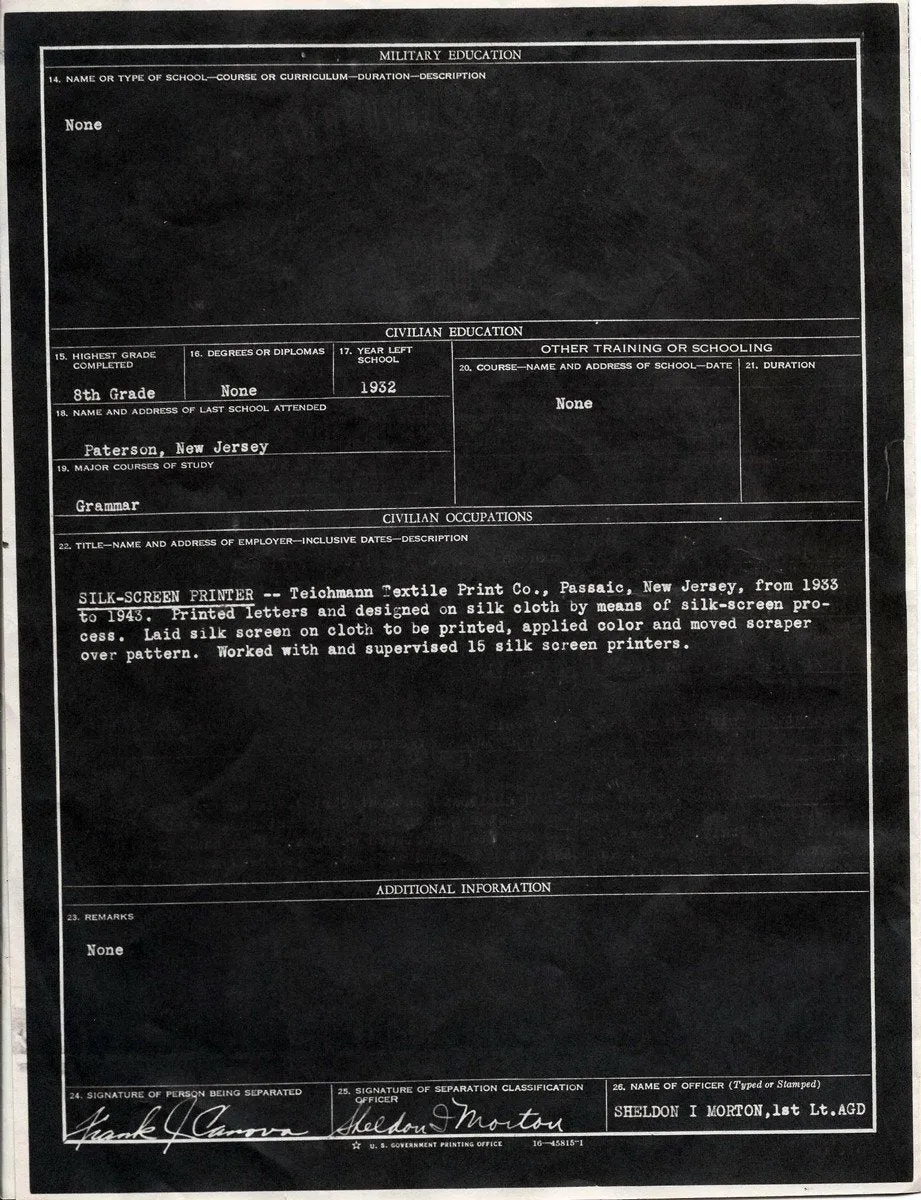

Original Separation Qualification Record

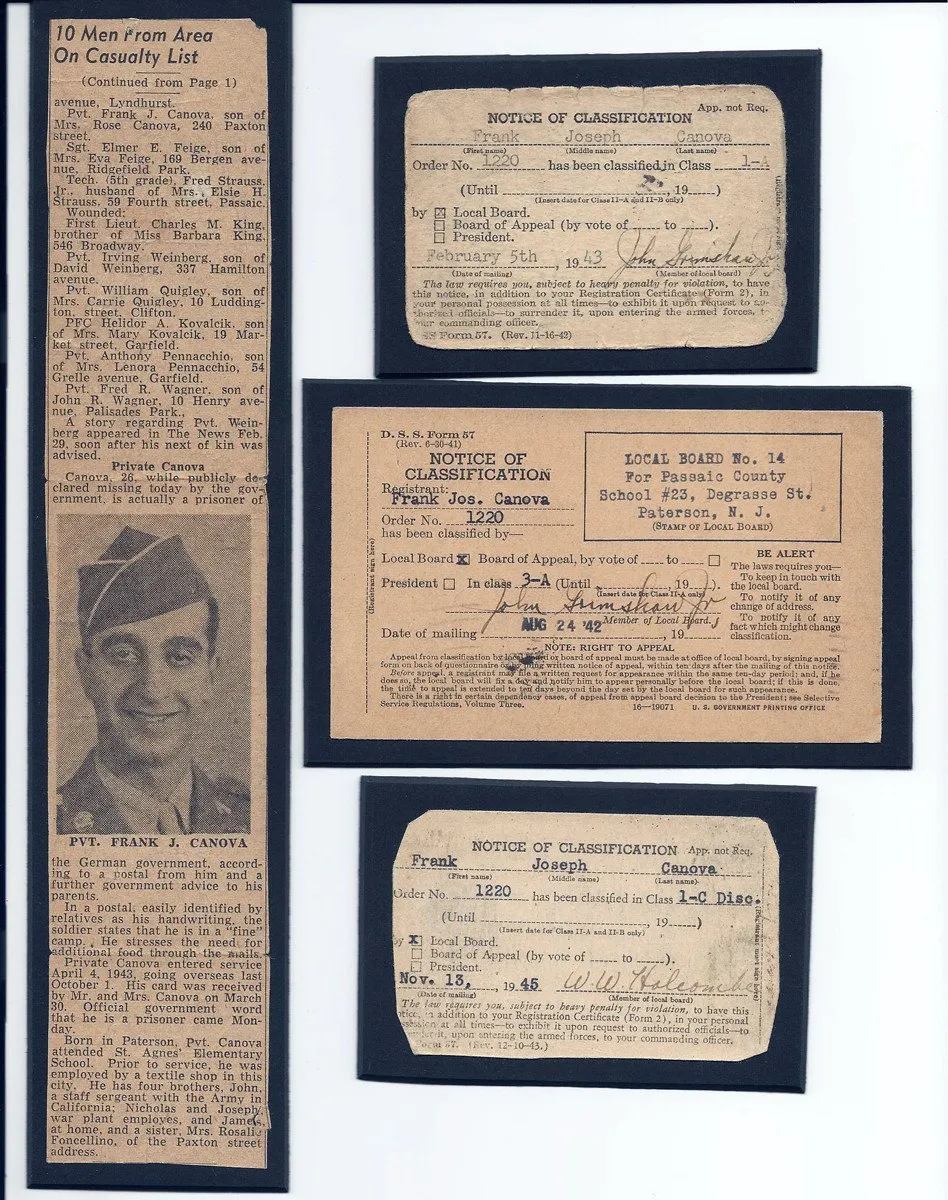

Three Original Selective Service System Notice of Classification cards from August 1942 (3-A), February 1943 (class 1-A), November 1945 (1-C Discharged)

An original newspaper cutting that reads- 10 Men from Area on Casualty List. Canova, 26 [photo of Frank Canova] while publicly declared missing today by the government, is actually a prisoner of the German government, according to postal from him and further government advice to his parents. In postal, easily identified by relatives as his handwriting, the soldier states he is in a fine camp. He stresses the need for additional food through the mails. Private Canova entered service April 4, 1943, going overseas last October 1. His card was received by Mr. and Mrs. Canova on March 30. Official government word that he is a prisoner came Monday.

The Original U.S. Army letter dated 5 may 1945 to Private Canovas mother Rose which reads- Dear Mrs. Canova: The Provost Marshall has directed me to reply to your letter of 25 April 1945, regarding your son, private Frank J. Canova. The records in the American Prisoner of War Information Bureau indicate that he is interned as a prisoner of war by the German Government at Stalag 2-B, Germany. His prisoner number is 270728. According to the Geneva Convention of 1929, the German Government is required to evacuate United States prisoners of war from combat zones to regions where they will be out of danger. Recent reports indicate that the German Government has transferred to the interior of Germany a large number of United States Prisoners of war who were located in areas which have lately become combat zones. it appears the the United States prisoners of war who were held at Stalag 2-B, Germany, have been transferred to prisoner of war camps in Central and Southern Germany. Since no information has been received as to individuals transferred, the correct address for letter mail remains Stalag 2-B, Germany. Please be assured that the War Department realizes your anxiety regarding your sons welfare. Any information concerning him will be forwarded as soon as it is received. Sincerely Yours, HOWARD F. BRESEE, Colonel, CMP, Director, American Prisoner of War Information Bureau, Provost Marshal Generals Office.

Various Veterans Administration correspondence.

Contrary to Franks letter to his parents Stalag 2-B was not a fine place in fact it is notorious as one of the harshest most violent POW camps in WWII. Stalag II-B was a German World War II prisoner-of-war camp situated 2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi) west of the village of Hammerstein, Pomerania (now the town of Czarne, Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland) on the north side of the railway line.

In August 1943 the Stalag was reported as newly opened to privates of the US ground forces with a strength of 451. The Hammerstein installation acted as a headquarters for work detachments in the region and seldom housed more than one fifth of the POWs credited to it. Thus at the end of May 1944, although the strength was listed as 4,807, only 1,000 of these were in the enclosure. At its peak in January 1945, the camp strength was put at 7,200 Americans, with some 5,315 of these out on 9 major Arbeitskommando ("Work Companies).

The camp sprawled over 25 acres (10 ha) surrounded by the usual two barbed-wire fences. Additional fences formed compounds and sub-compounds. Ten thousand Russians were detained in the East Compound, while the other nationalities 16,000 French, 1,600 Serbs, 900 Belgians and the Americans were segregated by nationality in the North Compound. Within the American enclosure were the playing field, workshops and dispensary, showers, and delouser. At times more than 600 men were quartered in each of the three single-story barracks 45 feet (14 m) wide and 180 feet (55 m) long. Despite these extremely crowded barracks, conditions contrasted well with the Russian barracks which held as many as 1,000 POWs apiece. Barracks were divided in two by a centre washroom which had twenty taps. Water fit for drinking was available at all hours except during the last two months when it was turned off for part of the day. Bunks were the regulation POW triple-decker bunk beds with excelsior mattresses and one German blanket (plus two from the Red Cross) for each man. In the front and rear of each barracks was a urinal to be used only at night. Three stoves provided what heat there was for the front half of each barrack, and two for the rear half. The fuel ration was always insufficient, and in December 1944 was cut to its all-time low of 26 pounds (12 kg) of coal per stove per day. On warm days the Germans withheld part of the fuel ration.

Treatment was worse at Stalag II-B than at any other camp in Germany established for American POWs before the Battle of the Bulge. Harshness at the base Stalag degenerated into brutality and outright murder on some of the Kommandos. Beatings of Americans on Kommandos by their German overseers were too numerous to list, but records show that 10 Americans in work detachments were shot dead by their captors.

In autumn of 1943, when Hauptmann Springer was seeking men for work details, American NCOs and medical corpsmen stated that according to the Geneva Convention they did not have to work unless they volunteered to do so, and they chose not to volunteer. At this, the German stated that he did not care about the terms of the Geneva Convention, and that he would change the rules to suit himself. Thereupon, he demanded that the POWs in question fall into line and give their names and numbers for Kommando duty. When the Americans continued to refuse, Springer ordered a bayonet charge against them. At the German guards' obvious disinclination to carry out the command, Hauptmann Springer pushed one of the guards toward an American, with the result that soon all POWs were to line up as ordered.

Typical of the circumstance surrounding the shootings are the events connected with the deaths of PFC Dean Halbert and Pvt. Franklin Reed. On 28 August 1943 these two soldiers had been assigned to a Kommando at Gambin, in the district of Stolp. While working in the fields, they asked permission to leave their posts, to relieve themselves. They remained away from their work until the work detachment guard became suspicious and went looking for them. Some time later he returned them to the place where they had been working and reported the incident to his superior. Both of the Kommando Guards were then instructed to escort the Americans to the Kommando barracks. Shortly after they had departed, several shots were heard by the rest of the Americans on the work detachment. Presently the two guards returned and reported that both Halbert and Reed had been shot dead for attempting to escape. The guards then ordered the other American POWs to carry the bodies to the barracks.

On another Kommando, the Germans shot and killed two Americans, stripped them and placed the bodies in the latrine where they lay for two days serving as a warning to other POWs. Eight killings took place in the latter months of 1943, one in May 1944 and another in December 1944. In almost every case the reason given by the Germans for the shootings was "attempted escape". Witnesses, however, contradict the German reports and state that the shootings were not duty; but clear cases of murder.

Except for housekeeping chores benefiting POWs, no work was performed in the Stalag. All men fit to work were set out to Kommandos where conditions approximated the following: A group of 29 Americans were taken under guard to a huge farm 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from Stolp, where 12 French POWs were already working without guards. Americans were billeted in a section of a large brick-floored barn. Adjoining sections were occupied by pigs, cattle and grain. POWs slept on double-decker bunk beds under two blankets. The French had a small building of their own. Guards lived in a small room opening onto the Americans' quarters.[1]

Each day the men rose at 06:00 and breakfasted on Red Cross food and potato soup, bread and hot water (for coffee) which they drew from the farm kitchen. At 06:30 they washed their spoons and enameled bowls and cleaned their barracks. They shaved and washed themselves in three large wash pans filled from a single spigot which gave only cold water. The outdoor latrine was a 3-seater. At 07:00 they rode out to potato fields in horse-drawn wagons driven by "coldly hostile German farmhands" who would welcome the opportunity to shoot a "kriege." Under the watchful, armed guards they dug potatoes until 11:30 when they rode back to the farm for the noon meal. This consisted of Red Cross food supplemented by German vegetable soup. Boarding the wagons at 13:00, POWs worked until 16:30. The evening meal at 17:00 consisted of Red Cross food and the farmers' issue of soup, potatoes and gravy. After this meal they could sit outdoors in the fenced-in pen of 30 feet (9.1 m) by 8 feet (2.4 m) until 18:30, after which the guard locked them in their section for the night.

On Sundays, the guard permitted POWs to lounge or to walk back and forth in the "yard" all day, but they spent a good deal of their time scrubbing their barracks and washing their clothing. Sunday dinner from the farm usually include a meat pudding and cheese. Once a month each POW received a large Red Cross food box containing four regulation Red Cross parcels. These were transmitted to distant Kommandos by rail and to nearby units by German Army trucks. Parcels were stored in the guards' room until issued. The average tour of duty on a farm Kommando lasted indefinitely. On other work detachments it lasted until the specific project had been completed.

On 28 January 1945, POWs received instructions to be ready to evacuate the camp at 08:00 hours the following morning. Upon receipt of these instructions, M/Sgt. John M. McMahan, the "Man of Confidence" (MOC) (a prisoner selected to liaise with the camp authorities) set up a plan of organization based on 25-man groups and 200 man companies with NCOs in charge. On the day of the evacuation, however, POWs were moved out of camp in such a manner that the original plan was of little assistance. German guards ordered POWs to fall out of the barracks. When 1,200 men had assembled on the road, the remaining 500 were allowed to stay in the barracks. A disorganized column of 1,200 marched out into the cold and snow. The guards were considerate, and Red Cross food was available.

After the first day, the column was broken down into three groups of 400 men each, with NCOs in charge of each group. For the next three months, the column was on the move, marching an average of 22 kilometers (14 mi) a day 6 days a week. German rations were neither regular nor adequate. At almost every stop McMahan bartered coffee, cigarettes, or chocolate for potatoes which he issued to the men. Bread, the most important item, was not issued regularly. When it was needed most it was never available. The soup was, as a rule, typical watery German soup, but several times POW got a good, thick dried-pea soup. Through the activity of some of the key NCOs, Red Cross food was obtained from POW camps passed by the column on the march.[1]

Without it, it is doubtful that the majority of men could have finished the march. The ability of the men to steal helped a lot. The weather was atrocious. It always seemed to be either bitter cold or raining or snowing. Quarters were usually unheated barns and stables. Sometimes they slept unsheltered on the ground; sometimes they were fortunate enough to find a heated barn. Except for one period when Red Cross food was exhausted and guards became surly, morale of the men remained at a high level. Practically all the men shaved at every opportunity and kept their appearance as neat as possible under the circumstances. From time to time weak POWs would drop out of the column and wait to be picked up by other columns which were on the move.

Thus at Dahlen on 6-7 March the column dwindled to some 900 American POWs. On 19 March at Tramm, 800 men were sent to work on Kommandos, leaving only 133 POWs who were joined a week later by the Large Kommando Company from Lauenberg. On 13 April the column was strafed by four Spitfires near Dannenberg. Ten POWs were killed. The rest of the column proceeded to Marlag X-C, Westertimke, where they met the men they had left behind at Stalag II-B who had left on 18 February, reached Stalag X-B after an easy three day trip, and then moved on to adjacent Marlag X-C on 16 April. Westertimke was liberated by the British on 28 April 1945.